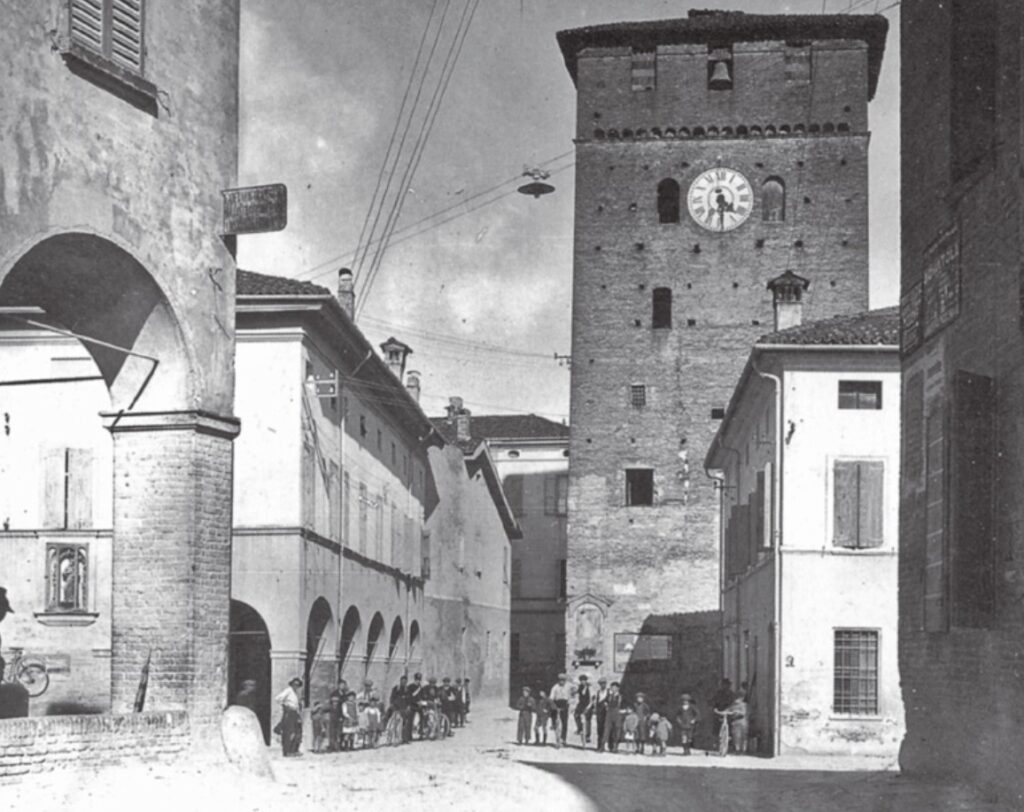

Let’s start from the end, from the slightly crazy gesture for which everyone remembers Eliseo Zoboli: the long voluntary exile inside the Torre dei Modenesi. A secession from the Nonantola society that lasted uninterruptedly for 14 years, from 1926 to 1940, the year of Zoboli’s death.

But what led a union leader, former councilor, one of the best known and most respected people in Nonantola to retire forever, until his death, in the town tower? Was it a surrender or a gesture of self-affirmation? Did he want to hide or did he want everyone to see him?

It would certainly seem the gesture of a madman or a mythomaniac, if we did not try to reconstruct how Via Eliseo Zoboli ended up inside the tower. My memories are limited and the only sources I draw from are some, very few, historical reconstructions, the stories of my father and the impressions I have left from when I was a little boy and I used to pass, with a mixture of fear and attraction, under the Torre dei Modenesi, aware of the secret it held. This story sure deserves better studies and researches. I hope someone who has the skills and the means to carry them on will get interested.

Nicknamed “al cinno”, which in Bolognese dialect means “the child”, probably because he was of small build, Eliseo Zoboli was not born in Nonantola: he arrived in Nonantola when the family, of peasant origin, moved there from Castelfranco Emilia, in the second half of the nineteenth century. At that time, the peasants, the majority of the Nonantolan population, were used to living and working in extremely harsh conditions. The summer seasons of exhausting work were followed by cold winters and sometimes hunger. The houses in which peasant families spend most of their time were damp, with little air, unhealthy and above all very cold.

And among the poor peasants, day laborers were the poorest of all, those most exposed to the designs of fate. Unlike sharecrop farmers, who enjoyed agreements with landowners that today we would define as “permanent” (although without holidays, nor cover for illnesses and accidents), day laborers were hired, as the name suggests, on a day-to-day-basis. Translated: the day you worked you ate, but if you didn’t work (due to rain, frost, the end of pruning or due to an illness that forces you to stay in bed) then there was no food, neither for yourself nor for your children.

There were still no parties or organizations that protected their interests and they themselves were struggling to get organized in order to claim more bearable working and living conditions. The church itself, as a whole, hindered their emancipation. Most of the chaplains and archpriests of Nonantola tried to cool down the hot spirits of their parishioners and stifle their urges to get organized: that hard life was not imposed by the masters, they used to repeat in their sermons, but by the good God from whom everyone, masters and peasants depended. If there was to be a reward for one’s efforts, it was not in this life that it had to be sought.

But between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, something began to change. The first “resistance leagues” of laborers and “birocciai” (the drivers of the “biroc”, the carts pulled by mules, horses or oxen) were formed. These were associations that tied the workers together, literally uniting them. Together they decided the hourly rates and the hours of work, together they presented themselves to the bosses so as to have greater bargaining power. Unity is an indispensable condition to create “resistance”, that is, to fight with the counterparts (agrarian bosses and landowners), and to get more dignified working conditions.

And things started to change mainly for two reasons: because the laborers got organized and because they started fighting. Examples of organization were the leagues I mentioned before, but also labor chambers, employment exchange offices, producers’ and consumers’ cooperatives, wine cooperatives. Examples of struggle were obviously strikes, both traditional and “reverse” strikes, experienced especially after World War II. In traditional strikes, workers cross their arms to demand better wages, more adequate working hours and tools; in “reverse” ones the unemployed work, unpaid, on public or private land to show that the jobs they were demanding exist, there is work to do and everyone could benefit from it: the construction of roads and canals, reclamation works, the introduction of new cultivation techniques, and so on. There is no time to describe all these forms of organization and struggle, but their creative force would still have a lot to teach to today’s workers and unions!

In Nonantola Eliseo Zoboli is one of the protagonists of this season of organization and struggle. My father was semi-illiterate, but in his poor culture he had a deeply rooted socialism. It was Cinno Zobel himself who had showed him that road, a man who knew how to find the right words to speak to laborers.

In 1903, Cinno and other leaders of the resistance league, after forty days of strike, got to do some reclamation work in the area. In 1904 they organized the first consumers’ cooperative. Under the pressure of these initiatives and these movements from below, in the same years the Municipality of Nonantola set up a charity kitchen to relieve hunger pangs during winter and began the construction of the village sewing system.

Thanks to these achievements and to the improvement in the yield of cultivated land, these organizations began to obtain consensus and participation among the farmers and, encouraged by this support, Eliseo Zoboli in 1914 became councilor with responsibility over agriculture and public works in one of the first socialist administrations.

But within a few years, the advent of Fascism blocked these experiments of democratic participation of the poorer classes in Nonantola, as everywhere else. And Zoboli, who at that time held a prominent position in the local workers and socialist movement, was targeted by the Fascists, who initially tried to bring him on their side, into the Fascist leagues and trade unions; then, given his intransigence, they began to isolate and attack him. The headquarters of Nonantola’s labor chamber were destroyed several times, and he himself was repeatedly beaten up.

Perhaps due to the consensus that agrarian Fascism obtained everywhere (and Nonantola was no exception), perhaps due to the support that state institutions such as the Prefecture, the Carabinieri, the Police offer to local Fascist groups, at this point Eliseo Zoboli, as a form of protest and disobedience, decided to retire into exile in one of the large rooms inside the Torre dei Modenesi, which in those years were used as a shelter for poor families and for destitutes.

When I was a child, I often heard my parents talking about Cinno, but they did it with a little fear, in a low voice. We lived on the first floor and they probably feared that indiscreet ears might hear their speeches in defense of Cinno. This was enough to end up in trouble.

Few friends had the courage to visit Zoboli in the tower, to give him something to eat, to update him on what was happening in Nonantola and in the world. The Fascists controlled all these movements. And it seems that every now and then they too entered his room to mock him and beat him up.

My father, who was a bell ringer at the Madonna della Rovere, had the task of going to the “search” every year for the feast of the Madonna. He had to collect and record the offerings in eggs, milk, wine, nuts that the peasants donated to the church. Bottles and proceeds from the sale were used to organize the party. I don’t know if it was true, but my father said some offers were given to support Cinno’s exile and he himself made sure to deliver them to him.

Already old (he was born in 1865) and worn out by the harsh living conditions inside the tower, at the end of the 1930s Cinno was admitted to Modena Hospital for stomach and heart problems. Apparently, it was the only time he came out of the tower. An epic scene reported by some witnesses describes Cinno who, once discharged from the hospital, got off the bus coming from Modena, stopped in the square of the seminary and walked unsteadily and hunched down along Via Roma to re-enter the tower, covered by the insults and the spit of the children incited by Fascist hierarchs. He wouldn’t live long. A few years or perhaps a few months later, in July 1940, after Italy had just entered the war, Eliseo Zoboli died in his hermitage in the heart of the village, hidden from view, but probably in the thoughts of many, admirers and enemies alike.

Se vuoi leggere la versione italiana dell’articolo, clicca QUI. QUI invece la versione in ucraino tradotta e letta da Yuliya Medvid e QUI la versione in punjabi di Hardeep Kaur.